The state and future of Art Platform Japan, according to a trio of American professors

February 9, 2023

Chelsea Foxwell, an associate professor of art history and East Asian languages and civilizations at the University of Chicago; Gabriel Ritter, an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara; and Bert Winther-Tamaki, a professor of art history at the University of California, Irvine; discussed the state and future of Art Platform Japan.

from left: Gabriel Ritter, Bert Winther-Tamaki, Odate Natsuko, Chelsea Foxwell

Art Platform Japan (APJ) has been active since 2018 as an initiative of the Japanese government’s Agency for Cultural Affairs (Bunka-cho). The idea has been to take diverse approaches toward developing Japan’s modern and contemporary art scene in a sustainable manner, such as through providing online resources and holding workshops for global participants.

For the Bunka-cho Contemporary Art Workshop held at the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya in September 2022, nearly 50 participants from around the world attended in person with many more people throughout the globe viewing live streams of the sessions.

APJ’s Contemporary Art Committee Japan organized the workshop at the Aichi Arts Center and took the opportunity to ask three participants about their thoughts on the program and APJ.

The three were Chelsea Foxwell, an associate professor of art history and East Asian languages and civilizations at the University of Chicago; Gabriel Ritter, an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara who is also the director of the university’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum; and Bert Winther-Tamaki, a professor of art history at the University of California, Irvine.

Contemporary Art Committee Japan member Odate Natsuko of the NPO Arts Commons Tokyo moderated the wide-ranging discussion over lunch on September 24.

The following are edited excerpts of their conversation.

Translations of selected Japanese art-related texts

APJ: We’ve translated in English nearly 100 important texts that haven’t been translated from Japanese. What do you think about this kind of translation initiative?

Bert Winther-Tamaki

Bert Winther-Tamaki

Bert Winther-Tamaki: Kojima Kaoru has some interesting texts on feminist perspectives of modern Japanese art. One was translated, the rest of them I think hadn’t been selected. Adding some of her other writings would also be very beneficial, I think, because this resource is still new and is likely to become an important mainstay for research of Japanese modern and contemporary art overseas.

When we teach this material in English at our home institutions, we can’t teach a topic if there’s no serious, engaging text in English to have our students read.

You really can’t make do with the text of a press release or something like that. When I put together a syllabus, I select topics and one of the criteria for including or not including a topic is whether there is a good text in English about that topic.

Chelsea Foxwell: Whether there’s something good to assign.

Winther-Tamaki: It has to be well translated, in reasonably good English, and has to engage the art to important historical issues. There are things that are available, but often they don’t rise to that level.

Odate Natsuko: It is also our aim to improve the quality of English.

Odate then mentioned the process taken by APJ.

After a text is selected by the committee for translation, a translator is found. The translation is then cross-checked by someone familiar with the topic. On some occasions, that person is the original writer of the text. Then it goes back to the translator before being edited and proofed. Fact-checking is done throughout the process before it is posted online on the APJ website.

Winther-Tamaki had recently finished translating a selected text for APJ (My Art Pedagogy by Kitagawa Tamiji).

Winther-Tamaki: When I was requested to do this translation, I received a lengthy set of guidelines that are very interesting. I think it was written by Andrew Maerkle and Reiko Tomii. It spells out all kinds of interesting suggestions for thorny translation problems. The text I was translating had a problem. The author made a blatant geographical error. He said the Andes Mountains were in North America. So, what do you do in a case like that? This translation project has been attacking these problems in a very sophisticated way. That makes a difference.

Odate: What do you think of the themes for the project?

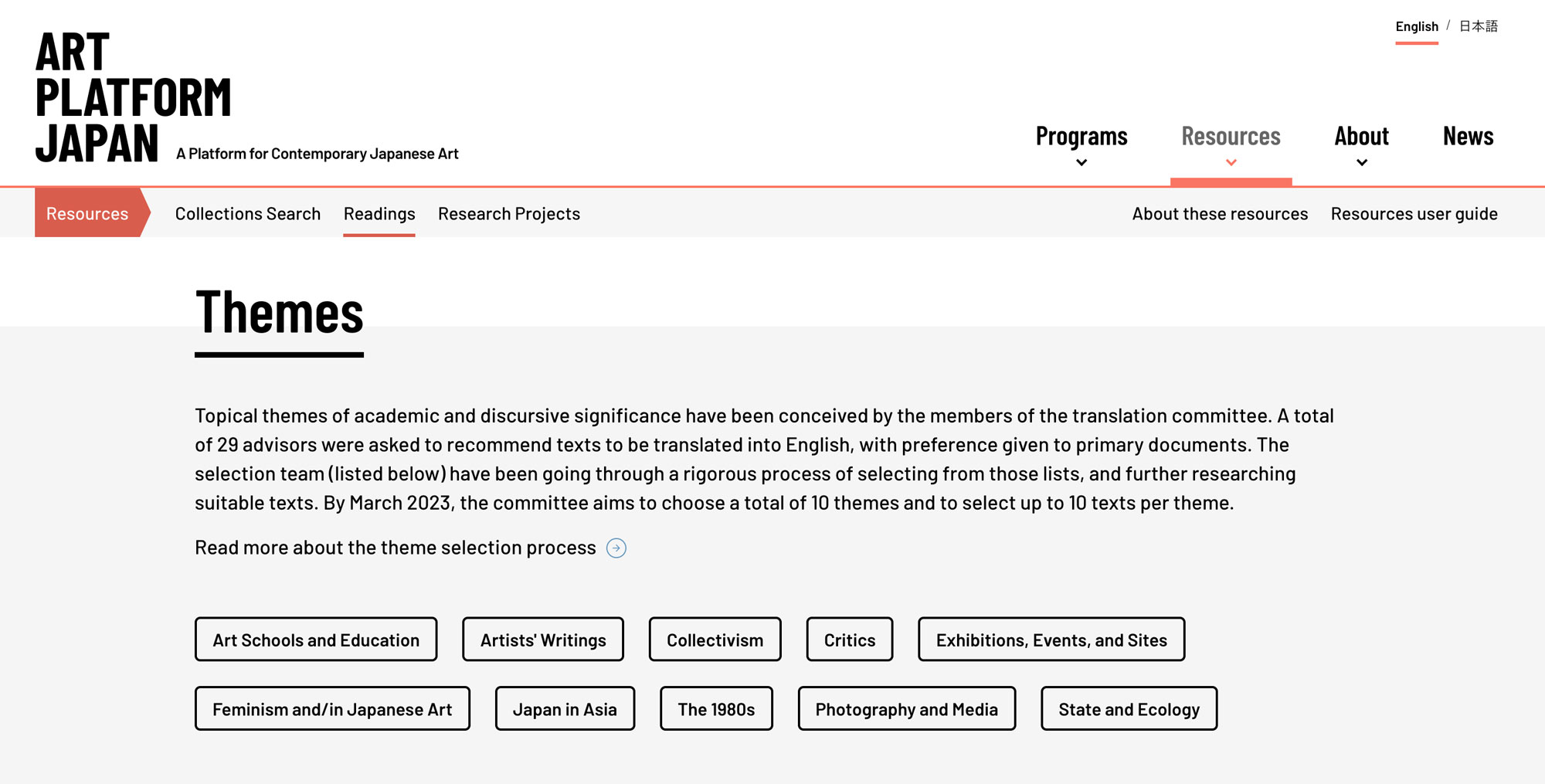

https://artplatform.go.jp/resources/readings/themes (The image as of December 2022)

https://artplatform.go.jp/resources/readings/themes (The image as of December 2022)

Winther-Tamaki:Ecology is one?

Odate: Yes, State and Ecology.

Winther-Tamaki: I actually didn’t like that one. I work on ecology and wasn’t sure about including the state in with ecology. Other things that were there didn’t look like what I would call ecology. Urbanism and Environment, or something like that, would make more sense to me.

Gabriel Ritter: The 1980s is one.

Winther-Tamaki: That’s a really good one.

Ritter: Speaking from a museum curator perspective, not so long ago I proposed a show on the global ’80s, and the response from the museum administration was: Why would anyone be interested in the ’80s? My thought was, well, because of all the world-changing events that happened at that time. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the birth of the internet, and so on.

Having texts that expand on the 1980s from a Japanese perspective would be very helpful in that regard.

We’re closely related to the Art Platform Japan project, but how is the Bunka-cho promoting or getting the word out about these translations? It’s worth connecting with researchers and professors. This is an important way to know that this resource is out there.

The three professors suggested using social media to promote and connect the texts to researchers and others likely to use the resources.

Books in print versus online databases

Foxwell: One of the few book-length works on premodern Japanese art that has been published in English is Tsuji Nobuo’s Kisou no Keifu [Lineage of Eccentrics in 2012] by Kaikai Kiki [artist Takashi Murakami’s company]. They hired a PhD student at Columbia at the time, Aaron Rio, who’s now a curator at the Met. [Rio is the associate curator of Japanese art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.] Shionoiri Yayoi [an art lawyer and strategist] was in New York at the time and she encouraged Aaron to do it.

Ritter: He was the assistant curator of Japanese art at Mia [Minneapolis Institute of Art] when I was there. He helped acquire some amazing objects and did some fantastic shows at that time.

Foxwell: It shows how having one book translated, if it’s the right book, it’s a really big deal.

Chelsea Foxwell

Chelsea Foxwell

Ritter: Is Art Platform Japan thinking to maybe publish the translated works?

Sometimes you find these almost dictionary-like publications on tracing paper that are incredibly dense. Having a physical copy published and located in the reference section of libraries worldwide would be useful to researchers. Librarians can then point students and researchers toward this reference material, which they might otherwise not know exists if they are just scouring the internet.

APJ: We translated KuroDalaiJee’s Anarchy of the Body and History of Japanese Art after 1945, both of which will be published next year by the Leuven University Press.

Winther-Tamaki: That’s going to be a very important publication.

Ritter: This is very much in an academic bubble, but I think it will help a lot of students and researchers. Having the APJ website as a known resource for research libraries at multiple college and university campuses could be really important.

On multiple occasions I’ve accessed the online database for works in the Japanese national museum system. It’s really rudimentary, but you put in the artist’s name and sadly it only gives you text, and once in a while it has an image. But sometimes this basic information can be useful.

Winther-Tamaki: That’s part of the Platform, right? Expanding that?

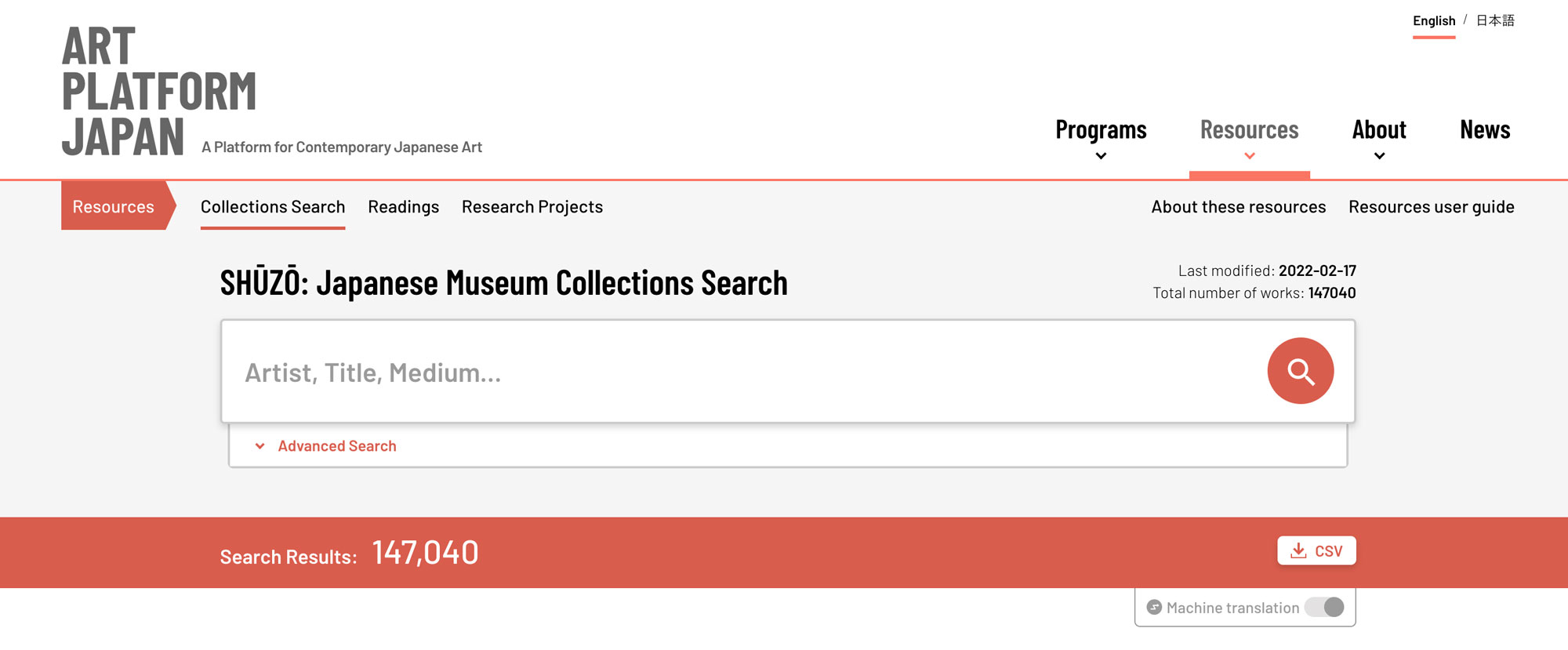

Odate: Oh, yes, the database, called Shūzō.

https://artplatform.go.jp/resources/collections (The image as of December 2022)

https://artplatform.go.jp/resources/collections (The image as of December 2022)

Winther-Tamaki: I think that’s in the process of being vastly improved.

Odate: So that’s our main kind of connection for the database and the artwork to go directly to the artist reference. Something we’re trying to work out is so you can search for an artist reference and find artwork and all the documentation.

Foxwell: One problem that the libraries have with digital resources is the link often moves over the years. If a book comes out, like if you published an anthology of translations, they know what to do with that. They buy it, it goes into the collection, you can search it. Now they even index the table of contents, so if that book contains ten artists and that student is interested in one of those artists, and they search it, it will come up. But if it’s a website, nobody knows what the website does, nobody knows that it exists.

They’ve told me, if you find a good database, let us know and we’ll put it in our library catalogue as if it was a book. However, then after three years, the link moves, and it doesn’t work anymore. Or even though the database is in there, if you search, you don’t know what the database is for.

APJ: We have also created a database of records of Japanese contemporary art exhibitions held at art museums in Japan and abroad. And have collected and published on the web basic information on art galleries since 1945. What do you think?

Foxwell: Oh, yes, my student used that in helping me compile my list [for her presentation “Recent Trends in U.S. Museum Exhibitions of Postwar and Contemporary Japanese Art: With an Eye to Fostering Growth and Diversity” at the Bunka-cho Contemporary Art Workshop earlier in the day].

Ritter: I’ve looked at the same one. It’s quite extensive and impressive.

Images and copyright issues

APJ: The Shūzō search system currently has data on artworks in the collections of 152 major museums in Japan. What do you think of it?

Foxwell: More pictures. Need more pictures. Bigger and more.

Winther-Tamaki: That’s a real important thing. Frequently you find a work listed, but it’s so frustrating because the names are listed, but you can’t see the work. Or sometimes there’s a tiny picture. What can you do with a tiny picture? You can’t use it in a lecture.

Ritter: You can’t share it.

Foxwell: You can’t study it either.

Winther-Tamaki: So, the thumbnail image is not a good solution. It has to be high resolution.

Foxwell: It has to be like 600 by 800 pixels so at least you can put it in a PowerPoint.

Ritter: In the US system, we are often limited because of copyright. In the Japanese system, is there a size that’s acceptable for public use? In the US, there is a size online that’s agreed to, seen as being public domain. If it’s bigger than that, then you start to infringe on copyright. So, I don’t know if the Japanese system has the same. But having something that is PowerPoint-worthy would be important.

Winther-Tamaki: There are going to be legal issues. We’re not lawyers. But for our purposes, that’s the thing: If you can show it on PowerPoint, then you can really use it.

On a related topic, I’ve been going to a lot of libraries in Tokyo, and none of them allow scanning. You have to make a paper photocopy and take it into a convenience store and turn it into a jpeg.

Gabriel Ritter

Gabriel Ritter

Ritter: Even as a researcher at MOMAT [the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo] when I was on the Japan Foundation Doctoral Fellowship, I had to do that. I purchased my own scanner and all I was allowed to use were boxes of photocopies. I never was allowed to access the originals.

Winther-Tamaki: You know, that was many years ago now, right? But still, as of this week, no change. I was shocked. This year, I thought I could go in and do this work digitally. But no, you can’t. I don’t know what the law says, but it’s very tedious.

We’re accustomed to being able to go into a library in the US, pull a book off the shelf, and make a fantastic scan with an overhead scanner. Now that’s the norm.

The question is, what is the law? If the law says you can’t do it, then you can’t.

Ritter: But that seems to be an argument in favor of having the Bunka-cho being behind this project. If the government can’t make it happen, then nobody can.

Winther-Tamaki: Copyright law in the US hinges on whether you’re going to use it for commercial purposes or not. I wonder whether that is a factor in Japanese law too.

Ritter: It’s interesting the way you’re describing the system is maybe in the US how they would treat special collections. But these are not special collection resources. These are just books that are at the bookstore and the library.

Winther-Tamaki: I think that’s a good comparison.

Ritter: If there was a way to make a reference library or a set of texts openly accessible to the public to photograph or to scan, and it didn’t have to be so guarded, I think that would be helpful.

Promoting exchange, getting future generations connected

APJ: We have held workshops and lectures like the Bunka-cho Contemporary Art Workshop to promote exchange among curators in Japan and networking with curators overseas. A small number of scholars have also participated. What do you think?

Winther-Tamaki: I feel I’ve been a beneficiary of this. It’s helped me a lot. I’m shy. I don’t get to meet all these great people without a forum like this, so I appreciate it very much.

Ritter: Maybe it’s something that came out of the pandemic, but it’s such an enterprise with all of the streaming technology. The fact that the Bunka-cho supports that, and now it’s also livecast on Zoom or YouTube, and is being recorded. The earlier workshops were not archived in that way. It was much more of a closed-door session. And we weren’t talking about anything proprietary or being super-critical of anything. The fact that now it is more open to the public in that way is an important step forward.

Foxwell: And it’s online, so if you had to get up and do something, you can go back and see it. It’s really nice to have as a resource. I know that editing is a pain, and it costs a lot of money to edit those videos.

Ritter: The simultaneous translation for online viewers is so important.

Foxwell: It would be great to have something for graduate students and PhD students.

Foxwell then recounts attending an international workshop on Japanese art history for graduate students among universities in Japan, the US and other countries, where PhD students meet and exchange their research.

Foxwell: Professors from Japan and English-speaking places would come together. Part of it would be the grad students would present their research, dissertation topic, and partly they would have museum visits to go look at art. So, you’re with these really famous professors, and you’re with other PhD students in your cohort, and you’re going around to museums looking at art in storage.

Then Nicole Rousmaniere [professor of Japanese Art and Culture at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, University of East Anglia] told us, when I participated, all of you are going to be colleagues in the future. Because we didn’t know, we were just young people. And it’s so true.

There’re people in other countries that the only way I know them is because I was in this workshop with them. And they’re the leading Japanese art specialist in their country.

Extending this opportunity to the next generation would be so valuable. Because the problem with the one I did was there was no funding, there was no organizational structure. If I want to do it at the University of Chicago, then I have to find funding, I have to find staff to run it, and it’s too much work maybe for just one person.

Ritter: I remember coming to Japan for the research year and I was in a unique situation because I wasn’t associated with a university, I was associated with MOMAT. I became almost like a temporary worker there, but my research was my work. So, I kept mining the archive because I had daily access to it. But I wasn’t connected with other students in the same way. But then other students sort of knew I was in town, so we would connect at various kenkyu-kai [study groups].

To maybe have some of Bunka-cho’s support for those like you’re suggesting—

Foxwell: It can maybe have an artist’s studio visit or something hands-on. Because students can come together to have a reading group, but maybe there are some special things that will need facilitation.

Ritter: If Bunka-cho can support that type of initiative like they’re supporting this gathering, that would be great.

Foxwell: Because the general problem in the field of Japanese art history is the pipeline. I have students now who want to study contemporary art but they’re struggling to learn Japanese. And if graduate students can’t learn Japanese quickly, they won’t be able to get a PhD in Japanese art, I think. So, students need to be brought in to the study of the field earlier, in part through translated texts and other material available through APJ.

Odate Natsuko

Odate Natsuko

What will APJ become?

APJ: Art Platform Japan is an Agency for Cultural Affairs initiative rather than a museum or institution initiative, but the five-year term of Bunka-cho running APJ ends on March 31, 2023.

Winther-Tamaki: Well, it sounds like it’s going to be an institute. Then it’s going to continue and proceed with these types of functions. We would probably call it an institute.

Foxwell: A research institute?

Winther-Tamaki: I guess. Certainly, it’s doing valuable work and I hope that it continues.

Photos: Sengoku Ken (.new)

Edit & Text: Yung-Hsiang Kao