How to Use SHŪZŌ? Thinking with Artists about the practical uses of museum collection databases

March 26, 2023

Nariai Hajime and Soeda Kazuho, members of the Research Resource Committee, part of the Preparatory Office of the National Center for Art Research, sat down with artists Fujii Hikaru and Iiyama Yuki to discuss SHŪZŌ, a platform which enables users to search artworks across museum collections nationwide. Tezen Wakako, who is involved in the operation of SHŪZŌ, was present from Art Platfrom Japan. Together, they consider the present and future of databases. (Titles omitted)

At the National Art Center, Tokyo. From left, clockwise: Nariai Hajime (Curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo), Soeda Kazuho (Curator, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art), Tezen Wakako (Art Platform Japan), Fujii Hikaru (Artist), Iiyama Yuki (Artist).

At the National Art Center, Tokyo. From left, clockwise: Nariai Hajime (Curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo), Soeda Kazuho (Curator, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art), Tezen Wakako (Art Platform Japan), Fujii Hikaru (Artist), Iiyama Yuki (Artist).

What kind of research can be done with a database?

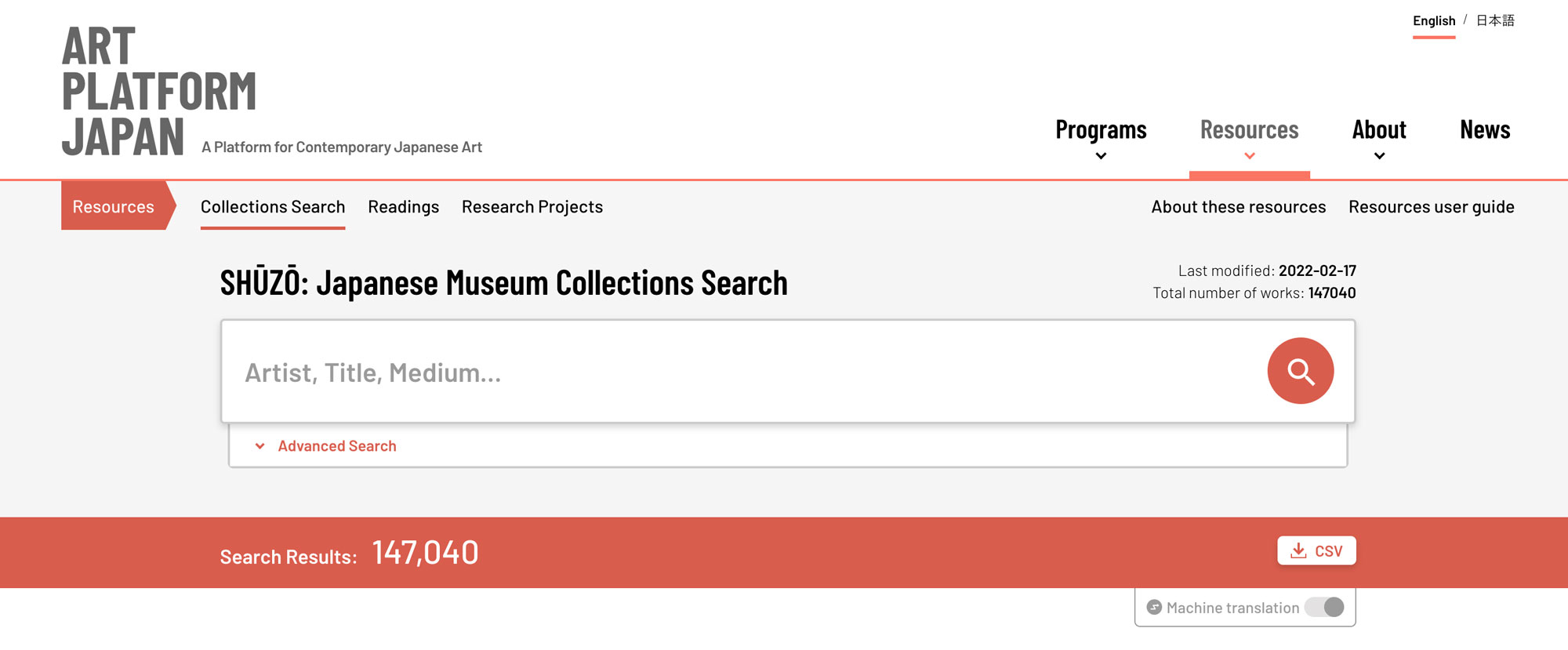

Tezen Wakako (below, Tezen): SHŪZŌ is a database of artists and their works from the Meiji period to the present. It was launched in March 2021 as part of the Agency for Cultural Affairs' Art Platform Project. Users can search 147,040 items from the collections of 152 museums across Japan, as well as obtain information on 2,170 artists (as of January 2023).

Japanese Museum Collections Search (SHŪZŌ) (Image taken January 2023)

Japanese Museum Collections Search (SHŪZŌ) (Image taken January 2023)

Nariai Hajime (below, Nariai):

Artists Fujii Hikaru and Iiyama Yuki are here with us today, as well as curator Soeda Kazuho from Aichi, Japan. We’re looking forward to discussing the future of SHŪZŌ.

Fujii-san and Iiyama-san, both of you make what’s referred to as research-based artworks. The first question I’d like to ask is: what role does research play in your art practice? What importance does it have? For example, Fujii-san, you recently had an exhibit on war paintings for which you did research using a database of artworks.

Fujii Hikaru (below, Fujii): That’s right. And going back even further, I had another exhibit in 2018 at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, called Travelers: Stepping into the Unknown, where I used the same method.

Nariai: This was Southern Barbarian Screens [Namban-ezu], right?

Fujii: Yes. Since this was a commissioned work, I wanted to have a sense of the space where it would be exhibited. SHŪZŌ didn’t exist yet at that time, so I just scrolled through the entire collections database of the four National Art museums (Union Catalog of the Collections of the National Art Museums, Japan). What caught my eye was Ishimoto Yasuhiro’s Photographic reproduction of Claude Monet's "Nympheas" (1980) . I thought, what is this? Why did he go all the way to the MOMA (Museum of Modern Art, New York) to photograph a Monet painting? When I looked into it, I found out that it was commissioned by the MOMA, and that they had also asked other photographers to photograph other works in the collection. And that’s how I found out about Narahara Ikkō’s work Photographic Reproduction of “Namban-byōbu” (1982).

Still image of Southern Barbarian Screens (2018). A film of Narahara Ikkō’s photograph of a magnified portion of Nanban byōbu (Collection of Lisbon’s Museu National De Arte Antiga) being taken out of storage and exhibited in the museum. Narahara and Fujii met through surveying The National Museum of Art, Osaka’s collection. | ©Fujii Hikaru

Still image of Southern Barbarian Screens (2018). A film of Narahara Ikkō’s photograph of a magnified portion of Nanban byōbu (Collection of Lisbon’s Museu National De Arte Antiga) being taken out of storage and exhibited in the museum. Narahara and Fujii met through surveying The National Museum of Art, Osaka’s collection. | ©Fujii Hikaru

Nariai: Is it helpful to have access to a database [of museum collections] when you are beginning a new work?

Fujii: Not always, but in this case it was the database that motivated me to do the research.

Soeda Kazuho (below, Soeda): Is that because of how accessible it was? I’ve heard that print catalogs are easier to take in at a glance.

Fujii: I guess it never occurred to me to ask the curator for a print catalog of the collection. I just scrolled through it in chronological order.

Soeda: I’d love to hear more details like that.

Nariai: Chronological order by collection year, or production year?

Fujii: Production year. In order from past to present.

Nariai: I see. Perhaps browsing through the whole catalog without looking for anything in particular can yield interesting discoveries.

Fujii: The interesting thing about a database is that it allows you to see what kinds of things you’re unconsciously drawn to. At the time, I was interested in the wartime period (193‒45), so I felt myself being pulled in that direction, but I actually ended up choosing a piece that wasn’t from that period.

When you take in the entire database at a glance, you begin to see new things

Nariai Hajime (Curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

Nariai Hajime (Curator, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

Nariai: Iiyama-san, do you ever look at data from museum collections?

Iiyama Yuki (below, Iiyama): Very rarely. But I have made artworks that have to do with [the concept of] museum artifacts. In Doing history! (2016, Fukuoka Art Museum) I used text and video installations to collect information about what visitors at the exhibit were saying and feeling in front of the work. That was the material that became A few conversations that took place in front of a collection.

Nariai: Were those conversations collected through interviews?

Iiyama: They were based on conversations that took place between volunteers who were leading guided tours through the museum, and participants in those tours. The Fukuoka Art Museum holds weekly interactive viewings led by volunteers, and I was there as a sort of passive participant. The four or five works discussed included Raphael Collin's By the Sea and Yanagi Miwa's Elevator Girl series. There were also statues of people related to the museum and the region that didn’t make it into the collection catalog.

Nariai:

So people were getting excited, talking about Kuroda Seiki and people like that?

modern Western-style painter who studied under Collin

Iiyama: Surprisingly, the reactions were much more raw. For example, one elderly woman said things like, "I don't like the motif of naked women [in these works]," or "Must be nice to have such a beautiful body,” as she gave the works a cold look. This was very interesting to me. Another person, an elderly man, looked at Yanagi Miwa's work and said "Look how energetically these women are working!" ...... These are honest reactions, and I thought it was important to take that [raw information] and turn it into a text of some kind, whether a novel or a play script, to show future readers that these are the kinds of conversations that were taking place in 2016.

Conversations that took place in front of the collection, commissioned by Fukuoka Art Museum using keywords of “history of the museum, present, future.”

Seven texts, a single channel video, and sound. 16’34”.

Photography: Yamanaka Shintaro (Qsyum!) | ©Iiyama Yuki

Conversations that took place in front of the collection, commissioned by Fukuoka Art Museum using keywords of “history of the museum, present, future.”

Seven texts, a single channel video, and sound. 16’34”.

Photography: Yamanaka Shintaro (Qsyum!) | ©Iiyama Yuki

Nariai: That’s very interesting.

Soeda: Is there anything in particular you’re researching now?

Iiyama: Recently I’ve been thinking of making a work about an incident whose witnesses are disappearing. I would like to use a visual format like a map, rather than a video.

Nariai: What kind of themes would it address?

Iiyama: Basically it would trace the migration of female sex workers across international borders, beginning in Japan. This includes women who became, and were forced to become, comfort women during the Asia-Pacific War, both in Japan and in the former colonies and occupied territories. What was everyday life like for people during their migration? What were their living conditions, what customs did they have, how did they dress? I would like to create a kind of pictorial map that allows us to get a sense of these specific details across time and regions. I know that some parts of it will be wrong or incomplete, but I think it’s important to try to visualize this history. At first I planned to search for the invisible traces of these women, but as I proceeded with my research, I began to think that a comparison to representations of other women during the same time period might also be important. For now, I’m planning to look at representations of women from the Middle Ages to the postwar period, so I’m grateful for the existence of this database. I think it will be useful for me to get a general overview.

To Tag? Or Not to Tag?

Iiyama Yuki (Artist)

Iiyama Yuki (Artist)

Nariai: How do you look up information when you’re doing research for an artwork?

Iiyama: Maybe with something like Japan Search? For example, if you do a Google image search with the terms "Indochina / Japanese / sex worker" you might find a number of historical images that fit the bill, but sometimes the captions for the images are done by a third party, and are incorrect. So then you have to look for the source of the image. I think public databases are more reliable in this respect because they’re built by experts. I don’t think SHŪZŌ currently has a way to search images, so I think it would be helpful if it could let you search for information more intuitively in the future.

Nariai: By intuitively, do you mean something that would allow you to search within a specific time period, for example?

Iiyama: I think so, yes. Right now, SHŪZŌ creates too strong a link between the artists and their work, which limits the way you can search for things in the database. It would be nice if it included other kinds of information that led the user to the artwork.

Soeda: So, the user might type in search terms like “women” and “representation” and then the database would pull up a whole queue of images in chronological order?

Nariai: Right, so basically tagging the images. I’ve gotten similar feedback in the past—for example, one museum was having an exhibit on railroads, and they wanted users to be able to search for the exhibit using the hashtag #railroads. It sounds convenient, but it’s actually very complicated to implement. Not because it’s technically difficult, but because the number of tags can increase exponentially depending on the interpretation [of the work], which could then influence how people understand the work. So even if [tagging items in the database] were possible, it’s debatable how helpful it would be.

Iiyama: Well, you could at least have basic tags, like #people or #landscape, or things like that. With the current configuration, you can really only search for works by putting in the artist’s name.

Soeda:

I think Iiyama-san is right that contemporary art tends to create a strong link between artists and their work. In SHŪZŌ, almost every work has an artist. But if you think about works from antiquity or archaeological artifacts, not every work has an artist. Which would of course completely change the interface and appearance of the database.

Using “SHŪZŌ” to search for information about an artist (Image from March 2023)

Using “SHŪZŌ” to search for information about an artist (Image from March 2023)

Who is the Database For?

Nariai: Listening to the two of you, it occurs to me that you’re both interested in information that’s been omitted from official accounts. Perhaps the database evokes a desire to look ‘behind the scenes,’ so to speak.

Fujii:

Well, at the end of the day, the database represents the winners of history. Everything’s neatly laid out for you. There are no surprise discoveries. So there is always a tension between the database and the artist.

I think the question to consider here is what kind of user we’re envisioning for it. For example, perhaps it would be better to tailor the database to researchers rather than artists—in which case it should be constructed in a way that supports research and criticism. But artists can use the database in a different way, look at the information with a more critical eye, and from a different angle.

Iiyama: Perhaps you could start by enhancing the database with images and videos of artworks referenced in studies and papers? I think a database that supplements textual information with other media would make it easier for people to use for their studies. For example, currently the works of important artists like Yamashita Kikuji cannot be viewed comprehensively, a database might completely change the way we view his work.

Nariai: What information is there about Yamashita Kikuji in SHŪZŌ?

Tezen: A quick search of the artist’s name yields about 793 results, but very few of those show us images of the artist’s work. Increasing images is something we’ll continue to work on.

Nariai: I’m interested in what Fujii-san said about there being a tension between the database and the artist. Museums often say they exist for the benefit of visitors, but who exactly do they have in mind? It’s not just the general public that visits museums, of course, but artists too. The museum wants people to look at one work, and have it lead to the next. That is one of its missions. What I’d like to ask, and this isn’t just about SHŪZŌ, is whether museums are providing information and materials that contribute to artists’ own activities.

Fujii Hikaru (artist)

Fujii Hikaru (artist)

Fujii: I’m grateful that you’re thinking of us artists who are active today, but …

Nariai: But…?

Fujii: But there is still a great deal of work to be done on the part of museums to rewrite historical descriptions in the archive, and to make the archive itself a more critical space. I would like to see the museum lay the groundwork to include works by women artists, minority groups, and artists who have passed away. Once they do this, then I think artists will have more confidence in the museum as an institution.

Iiyama: This might be straying from the topic a bit, but from the artist side, I would like to see some sort of system put in place to better support contemporary artists—for example, when national and public museums commission their work, paying them more in rewards and production funds, or hiring more full-time curators and staff. I would really like to see the overall infrastructure improved first. Right now, it’s basically a game of chicken—for both artists and curators, there’s such a bias when it comes to things like nationality, class, gender, disability, and ethnicity.

Nariai: Supporting contemporary artists is one of the goals of Art Platform Japan, so thank you for sharing that important perspective.

Soeda: These are all very important points. In principle, museums have an unlimited number of works and information that they want to include, and they try to cover as much as possible. As Fujii-san said, this creates one historical narrative that is well-known, publicly speaking, but the larger it becomes, the darker the shadow it casts. When Iiyama-san was talking about her project at Fukuoka City Art Museum, I kept thinking about what would happen if everything that visitors said in front of a work of art were automatically collected and archived. Would it really be a good idea to record everything like that? Even as I’m thinking about how to expand the database to make it a more interesting archive, I also feel a certain degree of hesitancy as well.

From Database to “Inspection”

Soeda: Since artists are copyright holders of the images in databases, they must be listed in them. Yet they are also users of those databases. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Iiyama: Recently, I was looking through the planning materials for an exhibit I was commissioned to do, and I noticed that all of the names of the artists scheduled to participate had their birth and death years listed alongside their names. I thought, "Wow, they’re expecting me to die, aren’t they? There’s no punchline to this story, but in any case, I’d feel more comfortable having my work treated like an antique jar made by an anonymous artist.

Nariai: Nariai: You’re opposed to [having your birth year] indicated?

Iiyama: I’m not opposed per se, it’s just more a question of, what convention is this based on? I just wondered where the practice actually came from. I guess I don't like the feeling that someday someone, I don't know where, will construct a certain narrative about me [based on that information]. In many researcher profiles these days, the birth year isn’t noted, right?

Nariai: From a historical perspective, I think listing the birth and death year [of the artist] is necessary. [Changing the topic slightly], I was thinking about how with video media, the work itself cannot be entered into the database—only a representative screen capture. Since you all both work with video materials, do you have any thoughts on this?

Fujii: I have no problem with that. They do the same thing with pamphlets and leaflets for exhibits.

Nariai: I know that in some cases, artists have made their video works available on Vimeo, YouTube, etc. Of course, each individual takes a different approach, but would you prefer to increase accessibility in this way, or are you uncomfortable with the idea of having your work be available to the public?

Fujii: The screen capture is just an access point into the artwork, one possible way of entering it. So I don’t necessarily think it’s a problem if the video itself isn’t available.

Iiyama: Technically speaking, the same is true for paintings—in the database, only an image of the painting is available, not the entire artwork.

Fujii: That’s very true. But where do you go from there? One time I went to the National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo to try and look at the backs of the war paintings there, but was told I needed to submit a request for ‘jukuran’. I’d never even heard of that term.

Iiyama: How do you write it?

Soeda: ‘Juku’ is written with the character for thoroughness, and ‘ran’ is written with the character for observing, examining. So, ‘jukuran’ means to examine or examine something thoroughly.

Iiyama: So, a request for a thorough examination?

Fujii: Yes. If you submit that, then you can go around the back of the museum where they store their collections and look at the piece.

Nariai: That’s right. If researchers wish to gain information beyond what is accessible to the general public, we ask that they first submit a request to inspect the work.

Iiyama: And if that procedure is followed properly, then can anyone see it?

Nariai: Yes, as long as there is a valid reason for it. A lot of museums have this rule. For example, if you want to copy or reproduce any work in the museum, you have to go through a similar process.

Fujii: I was writing the translator’s note to a monograph at the time——that’s what made me want to go and look at the piece. I’d come across something that really intrigued me.

Iiyama: I understand. The kind of artwork I make is referred to as "research-based," but mostly I just borrow research that other people have done and conduct interviews....

Fujii: I can easily spend a week in the storage room looking at all 30,000 items in a collection. That might sound kind of intense, but that’s just my personality. But I’m very aware that I’m an amateur in my own research field. I mostly rely on visual reasoning and sensitivity. That’s why I value collaboration with researchers who have previous experience and academic knowledge.

Iiyama: For artists, I think an online database is really just the beginning. As Fujii-san mentioned, it’s important to interact with archives and documents as physical objects, in actual spaces, and to talk with researchers, experts, and communities related to the material. Most artists aren’t experts in archival (historical) research, and many of them probably proceed through a process of trial and error. It’s difficult for amateurs to use primary sources correctly, and it’s easy to make mistakes. I assume Fujii-san must have gone through a lot of trial-and-error as well. It would be nice if the "request for inspection" mentioned earlier were more widely known.

Soeda: For instance, if users could look up an artwork in SHŪZŌ, and the search results automatically gave them a list of PDFs of relevant academic articles…

Fujii & Iiyama: That would be great.

Nariai: Along with SHŪZŌ, the APJ website is also preparing a bilingual database of bibliographic materials [related to the artworks]. Currently, the main focus is on commentary and criticism, so hearing you talk about this makes me think it would also be nice to include more research-based papers. It would be interesting to connect with academic research databases such as CiNii.。

If we could get to the level of Big Data…

Iiyama: Is it possible to include video data in the database?

Nariai: Technically speaking, it is. But SHŪZŌ has no plans to implement that as of now.

Iiyama: Speaking from an artist's perspective, I think there are basically two types of video works: those that can only be experienced in high-quality screening environments like museums or movie theaters, and those that can also be accessed through online distribution. I imagine that the screening environment is a major factor in whether a work can be distributed or not, but I wonder how that kind of nuance can be conveyed to the user of the database. Conversely, regarding deceased artists, I wonder who is in charge or deciding whether to release their works when their copyrights have expired…

Nariai: When the videos are embedded, the database takes on the role of a repository or backup. At the same time, this can call into question the restrictions for image use, as well as the ethical responsibility of those managing the database.

Soeda: Conveying nuance is one of the things that these databases are worst at. Both famous and unknown artists are equally represented as a single record. But sometimes databases can be used as rescue ledgers when the material has been destroyed by a fire or some other disaster, or when the materials are in a physically inaccessible location. When the paper catalog is lost, an online database can be used to restore the information and show what was there.

Nariai:

We’ve talked a lot about things that might make SHŪZŌ more interesting or convenient to sue, but I’d also like to reiterate the original intent behind the project. The ‘foundation’ that Fujii-san is talking about, the ‘beginning’ that Iiyama-san mentioned—those are the exact things we are trying to expand upon.

There is a lot of information in Japan that is open to the public but inaccessible. In fact, there is currently no place in Japan where you can view the entire catalog of items in art museums across Japan, even on paper. The fundamental idea behind SHŪZŌ's cross-search database is to compile this information. We mostly wanted to improve accessibility, which has been challenging even for researchers and those of us in the museum field who have to actually go and visit various museums and libraries on-site to learn about a particular collection. Those kinds of barriers are unnecessary.

Soeda: What criteria did SHŪZŌ use to select the museum collections that would be included in the database?

Tezen: We began by approaching museums who are members of the Japanese Council of Art Museums. We are also calling on art-related museums who are members of the Japanese Association of Museums. Those who responded to our request are listed in the database. If we receive information from smaller museums, we will compile the information in the database and make it available to the public.

Soeda: So [by that time] there’s already been quite a rigorous selection process.

Fujii:

I actually think the fact that the information is fragmented can be interpreted as a good thing, as a sign that things are becoming more decentralized. What do we have to gain by making everything connected? I will reserve judgment about the APJ as a state-led project at this point, but I’ll just say that when I look myself up in the database, for example, I find that only a small portion of my works are listed. For an archive to be fragmentary or incomplete in that way is odd, I think.

The interesting thing about archives is that they contain the ideas and perspectives of the people who made them. It’s not enough to have a few or a few dozen items. It has to be hundreds of thousands of items. I have used many different databases from around the world for my research, but I think the scale of SHŪZŌ is still too small.

Nariai: Too small?

Fujii: Yes. So if you are going to do it, it should be done more thoroughly.

Iiyama: I think it would be good to make it more visible, for example by including works from private foundations and collections.。

Nariai: Yes, that’s a good idea.

Iiyama: For example, in some cases materials might be collected [in a museum] but not displayed or used. Materials collected at the grassroots level by repatriates at the Port of Hakata were placed in the city's collection and then displayed in exhibition booths at public facilities, but those exhibits weren’t changed out for long periods of time.

Fujii: That's right. It may not be immediately obvious, but behind the scenes, many museums are quietly collecting material that proves how people were forced to give up their local customs by a particular government, or by external pressure. When you have enough of those collections, things that were invisible before can be seen more readily. The same can be said for private collections. The Ohtake Shinro exhibition (*now closed) currently being held at MOMAT (The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) is a case in point.

Soeda Kazuho (Curator, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art)

Soeda Kazuho (Curator, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art)

Soeda: One example we often give in our comparisons is library search systems. Libraries, no matter how small, have created similar databases. While the database itself is managed by each library, it is very easy to search for books in libraries across the country.

Fujii: They’re all connected through a network.

Soeda: Yes, and the reason they can do that is because there are multiple copies of the same book. In contrast, art works are basically unique, so inevitably an art database will differ from a library’s. But speaking as an art history researcher——for example, I specialize in Miró——I wonder whether it would actually be so bad if you couldn’t find out with a single click which museums in Japan hold Miró’s works. However, as Fujii-san said, it is true that databases tend toward centralization.

Nariai: Even in a single work, there can be inconsistencies in the way it’s described in centimeters, millimeters, or other numbers, depending on the museum. Although in principle SHŪZŌ respects the data of individual museums and inputs them accordingly, I think it’s only natural that the idea of cross-search system is centralized. There’s also the question of how to maintain the regional qualities of a piece, or whether that’s even possible.

Soeda: Even if we were to receive a variety of data from each museum about the artworks, we could only include what would fit on the standardized lunch plate called SHŪZŌ. Locally, it may have been a rich full course, but unfortunately you can’t retain everything [at the level of the database].

Iiyama: Then again, it might be interesting to collect information that appears disorganized at first glance, and input it into the database alongside the artworks that have been collected. Even if just one PDF is attached to the work, it might completely change the way we understand it. Isn’t that something a researcher might be interested in as well?

Soeda: It is possible to put a link from each work to the holding museum database, so this could work if there is a database corresponding to that museum. However, in many cases, the only actual documents are in paper format, and when that’s the case, it can be hard to keep up…

How do you show something that’s invisible?

Nariai: It would be nice if we could have a sort of hub [of information] rather than collecting everything in one database. But as we look into information that has been omitted from official records, or sources of such information, isn’t there a possibility of this developing into conspiracy theories? Of being manipulated by bad research?

Fujii: I don’t really think there are conspiracy theories in academia. Researchers only write about things that have been settled, historically speaking, and when it comes to historical revisionism, the academic world just shrugs it off. However, in the post-truth era, there are artists who believe in [conspiracy theories] and get pulled into them, even though they know [those theories] can easily be disproved if they looked into it..... but I’m not sure there’s much we can do about that.

Iiyama: As with the earlier discussion of ‘jukuran,’ you have to contact actual people in order to see material, and this takes time. I wonder if conspiracy theories and paranoid delusions arise when there is nothing to intervene between the information and myself.

Nariai: To return to what we were talking about earlier, I think sometimes when you try to amplify a certain type of information, you end up introducing more bias. Those who are famous become more and more famous, while those who are unknown remain hidden forever. We have to be careful about what kind of information we’re talking about, since the attempt [to increase information access] can itself create more disparities.

Fujii: I think in this day and age, there is an acknowledgment that most collections and archives have been organized from the point of view of Western art, of the male, of the colonizer rather than the colonized, and I think it’s taken for granted that one will proceed in a way that is sufficiently self-aware. I think that both collections and archives are ultimately stories created by people. And when [museum] collections only include the work of famous artists, for example, it strengthens one particular narrative and reinforces one particular myth. The power that these kinds of narratives have has become very clear.

Soeda: The important thing is to be aware of the arbitrary nature of [those biases], and to be forthcoming in disclosing how the items for the database were chosen and according to what principles it’s organized. And going back to conspiracy theories, it’s often assumed that libraries and bookstores are neutral in how they display their books, but the reality is that, for example, they often foreground books that contain hate speech because those are the ones that tend to sell. Obviously this is also curation, and it’s impossible to completely avoid bias when curating something. But what’s important is to communicate who did the curating and with what intent. For example, the format of the database makes it appear flat and neutral, but something as simple as the way an artist’s name is spelled is the product of many discussions that have already taken place at the level of each museum—so in that sense, they are not necessarily uniform. 。

Tezen Wakako (Art Platform Japan)

Tezen Wakako (Art Platform Japan)

Tezen: Yes, when the museums submit the names of the artists, they are often spelled all kinds of ways, since each individual museum has their own rules about spelling and notation.

Nariai: When the spelling and orthography aren’t standardized, it might seem inconvenient, or give off the impression that we aren’t managing our information adequately. What we’re doing at this stage is simply acknowledging the different orthographic methods and finding a way to make them work together. Though I do think the history behind why things were intentionally transcribed differently is an interesting one.

To display something is to tell a story

Iiyama: Selection bias is already at play when the museum adds any new work to their collection. By disclosing, rather than hiding, the differences that already exist, a forum could be created for discussing the politics of the collection and exhibition of different artworks. I think that by making those differences visible, we can make works that people have traditionally overlooked more accessible.

Fujii: One thing to keep in mind is that facts and figures like the number of collections or exhibitions [a museum has] directly reflects the power of the market. The American and British art worlds display art in terms of quantified power. How many exhibitions does the artist have, how much power do they hold in society, what rank does the artist occupy? This kind of pecking order creates a certain dynamism. Can the Japanese art world, which has lagged behind in many ways, progress while also examining these side effects?

Nariai: Any database of museum collections will have traces of the "selection bias" that Iiyama-san mentioned, but the more data you have, the more possible it is to provide information that isn’t biased toward a particular set of values. It is up to the user [of the database] to harness that power. There was never any intention for SHŪZŌ itself to have power.

Soeda: At the museum where I work (Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art), we’ve received offers for image rights on art works that hardly anyone had paid attention to before, and that was all through SHŪZŌ. So it’s definitely having an effect.

Fujii: Sometimes the archive itself can offer a critical perspective. You can choose to spotlight only prominent artists with lots of collections and therefore reinforce the narrative that these artists are strong and great, but you can also choose to tell a different story.

Nariai: I agree. [The archive] can suggest connections between things that the museum hadn’t even considered, or voice opposition to things. We would love for more people to know that there are materials here that they can use.

Soeda: My hope is that the database will shed light on new stories that have been overlooked, and that we can find ways to make that happen. We’ve gathered so much information here. Compared to how things were back when I was a student, it seems like a dream come true. How do we successfully weave together many different stories and how do we find practical applications for them? We hope to continue to evolve this project with the input of our artists.

Participant Bios / Profiles

Iiyama Yuki: Artist

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture. She creates videos and installations using archives from the past, as well as interviews with people, as she is interested in how society and the individual influence each other. Her solo exhibition We walk and talk to search for your true home (2022, Tokyo Metropolitan Human Rights Plaza) included a video she created with her mentally disabled sister. The video work In-Mates (2021), which was scheduled to be shown as an accompanying project, was banned due to intervention by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government's Human Rights Department, and she is still seeking opportunities to show it through petition drives and other means. Her latest work is the video Eating the Patriarchy (2022), which was exhibited under the theme of domestic violence at the Mori Art Museum's Listening to the Sound of the Earth Turning: Wellbeing since the Pandemic.

Website

Soeda Kazuho: Curator, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art

Born in Fukuoka, Japan, Soeda has been a curator at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art since 2008. He was an assistant curator for the Aichi Triennale 2010-16 and 2022. He specializes in modern and contemporary art. Major projects include Between Botany and Art (2015), Aichi Art Chronicle 1919‒2019 (2019), and Joan Miró and Japan (2022). His articles include "(Anti-)Barcelona Painter, Joan Miró" and "Succulents and Photography: on the Edible Objects of Shimozato Yoshio."

Nariai Hajime: Curator, National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo

Born in Shimane Prefecture, Nariai worked as a curator at Fuchu Art Museum and Tokyo Station Gallery before taking up his current position in 2021. His research focuses on avant-garde art in postwar Japan. Major exhibitions include The World of ISHIKO Junzo: From Art via Manga to Kitsch (2011‒12, Fuchu Art Museum), Discover, Discover Japan (2014, Tokyo Station Gallery), and Parody and Intertextuality: Visual Culture in Japan Around the 1970s (2017, Tokyo Station Gallery). He is also a member of the Contemporary Art Committee Japan.

Fujii Hikaru: Artist

Born in Tokyo, Fujii examines the unique culture and history of various countries and regions through in-depth research and fieldwork, creating artwork that respond to the social issues of his time, mainly in the form of video installations. Recent works include The Japanese War Art 1946 (2022), a reproduction of an exhibition of Japanese war paintings held by the U.S. Army at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, and The Classroom Divided by a Red Line (2021), which highlights irrational forms of discrimination against refugees from Fukushima. He will exhibit his work in World Classroom: Contemporary Art through School Subjects, an exhibition commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Mori Art Museum (from April 19, 2023).

Website

Tezen Wakako: Art Platform Japan, heading Japanese Museum Collections Search (SHŪZŌ)

After working in contemporary art galleries, Tezen established TEZEN Inc. in 2008, and has served as the president of the organization since 2018. In addition to business management of art projects, she is involved in the construction and operation of artwork management systems for corporate and private art collections. In the Agency for Cultural Affairs Art Platform Japan, she has been in charge of Japanese Museum Collections Search (SHŪZŌ) since August 2019, as well as promoting Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibitions Research and Survey on Japanese Art Galleries from 1945.

Photos: Hosokura Mayumi

Edit & Text: Goroku Miwa

Translation: Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda